Imagine this: you go for a lovely meal with some friends. The food is delicious, the atmosphere is fantastic and of course, the company is just what you want. At the end of the evening, you float back to your car elated only to see you’ve been given a ticket and stuck with a massive fine.

How will you remember this evening?

Research suggests that despite spending most of the evening having a wonderful time, ending it on an unpleasant note ruins your perception of the whole event.

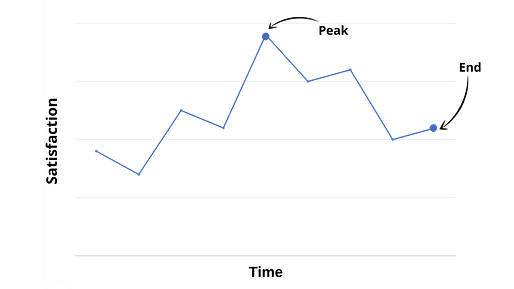

This is explained by the peak-end rule, coined by the Nobel Prize winner and pioneer of behavioural economics, Daniel Kahneman. He suggests that our memories are not an accurate reel of events but are in fact a series of highlights. How we remember an event is determined by the peak emotion experienced (negative or positive) and how it ends.

Experiencing self vs Remembering self

We have two selves; an experiencing self and a remembering self. The experiencing self lives in the moment. It remembers nothing and its mode of thinking is intuitive, quick, and unconscious. Each moment for the experiencing self lasts approximately 3 seconds.

The remembering self constructs the story of our lives. It collects our experiences and weaves them together into what becomes our memories. The intensity of emotion greatly influences the remembering self. Critically, the duration of the event or emotion does not matter.

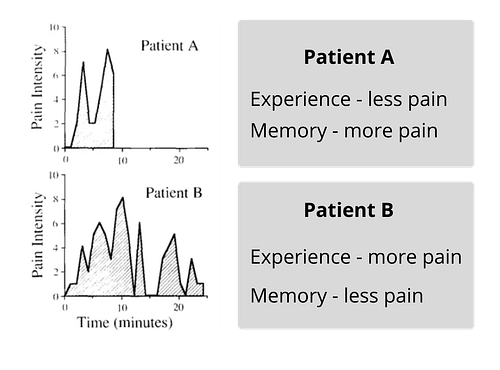

Redelmeier & Kahneman (1996) conducted some research where they studied patients undergoing a, at the time painful, colonoscopy. During each minute of their procedure, patients were asked to rate how much pain they were feeling on a scale of 1 to 10.

An hour after each colonoscopy they asked the same patients how painful they remember the whole procedure to have been. They followed up with them a month later, asking the same question.

Through their research, some interesting findings came to light.

- Patients that had vastly different lengths of surgery would rate them as equally painful if the highest level of pain and pain at the end were the same. This would occur despite the experiencing self having objectively suffered more pain in the longer operations.

- Increasing the length of the operation (inflicting more overall pain) but easing the pain at the end made the patient remember the ordeal as less painful overall.

Shape your memories

We can use this knowledge of the peak-end rule and the experiencing self vs remembering self to bestow ourselves with the Orwellian powers to control how we remember our experiences.

For example, when planning a holiday, structure it such that you spread out the most exciting parts, making sure to save the best till last. This will result in multiple peaks of joy, making the entire trip seem fantastic in your mind.

Interestingly, longer vacations have no benefit to how fondly you remember them as your remembering self barely notices the increased duration. While interviewing on Ted Radio Hour, Daniel Kahneman detailed how he was having so much fun on a holiday to Switzerland that he and his wife actually left a day early to avoid anything bad ruining their memory of it. If that’s not proof enough (and he’s a smart guy), I don’t know what is.

Some key things to keep in mind to make your memories great:

- Try and end your experiences on a high note and concentrate on the positive parts.

- Try not to let the minor discomforts or annoyances taint your recollection of the whole experience.

- When taking photos, even if you’re not enjoying yourself make it look like you are! You’ll remember the trip fondly when looking back on them (or at least be amused at your attempt to fool yourself!).

- If you journal, highlight the best parts of your day in your accounts. When you go back to read them, that’s what you’ll remember.

The peak-end rule can be applied in life and in business. Watch the excellent video below video by Adam Fraser who gives some examples of how to apply it in different situations.

Perhaps society has always known about the peak-end rule. Perhaps that’s why we save dessert for the end.

For more details check out Kahneman’s Ted talk.